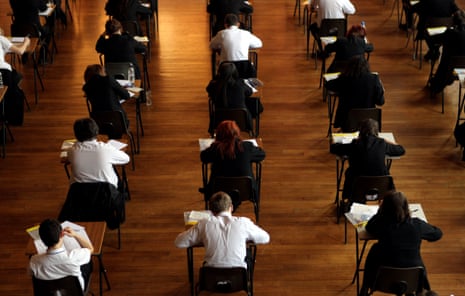

Students could be sitting some of their GCSEs and A-levels on a laptop by the end of the decade, according to England’s qualifications watchdog.

Amid complaints from pupils of writing fatigue in exams because their hand muscles “are not strong enough”, Ofqual is launching a three-month public consultation about the introduction of onscreen assessments.

Under the proposals, each of the four main exam boards will be invited to draw up two new onscreen exam specifications, targeting subjects with fewer than 100,000 entries. GCSE maths would therefore not be eligible but GCSE German would.

Already there are concerns about fair access to devices, cybersecurity and the potential for technical failure. Other issues include space requirements and larger desks to accommodate computers.

Ofqual said students would not be allowed to use their own personal devices for exams, and schools would be able to choose between onscreen and paper versions that would be offered as separate qualifications.

Sir Ian Bauckham, the chief regulator at Ofqual, said he was “definitely not gung-ho” about a shift to online assessment. The regulator insisted pen and paper would remain central to assessment in English schools and traditional GCSE and A-level exams would not disappear.

“We must maintain the standards and fairness that define England’s qualifications system,” Bauckham said. “Any introduction of onscreen exams must be carefully managed to protect all students’ interests, and these proposals set out a controlled approach with rigorous safeguards.”

Teachers say pupils who habitually use keyboards have lost handwriting stamina. “You do hear people say: ‘I don’t handwrite very much so my handwriting is poor’ or ‘I feel I can’t hold the pen for long enough’ or ‘My hand muscles are not strong enough’,” Bauckham said.

“On the other hand, you also hear counter-views that say actually, part of cognitive development is strongly associated with the actual mechanical process of handwriting, which is not the same as onscreen.”

Research carried out separately by University College London found students who used keyboards in exams got better test scores. Researchers tested state school pupils, comparing their scores in essays using handwriting and word processors under mock exam conditions. All pupils, including those with learning difficulties, made big improvements in tests when using word processors.

Only a tiny fraction of GCSE and A-level assessment in England is onscreen, including some elements of computer science exams. More broadly, students are able to use keyboards under exam conditions, if allowed by their school or centre, as reasonable adjustments for those with identified difficulties.

Bauckham said anecdotally, talking to students, he found views were evenly split, with half preferring onscreen assessment, while the other half preferred pen and paper, because it felt “more trustworthy”, “more serious”.

The education secretary, Bridget Phillipson, said: “We know interest in onscreen exams is growing, and aligning assessment with an increasingly digital world could bring valuable benefits, including for children with special educational needs and disabilities. But it’s also important any shift is phased, controlled and above all, fair.”

The consultation will run until 5 March and if approved, the new specifications will be in schools three years before first examinations in around 2030.

Steve Rollett, the deputy chief executive at the Confederation of School Trusts, said: “School trusts recognise the potential benefits technology can bring to assessment, but it’s vital that any changes are introduced carefully and with proper safeguards.”

Myles McGinley, the managing director of the Cambridge OCR exam board, which has been developing onscreen exams, said schools would “need a lot of support to narrow the digital divide, tackling the patchy access to the latest tech and specialist teachers.

“Equipping our young people to thrive in this changing world will require collaboration: more research, government support and regulatory guidance.”