Jain meditation

| Part of a series on |

| Jainism |

|---|

|

Jain meditation (Sanskrit: ध्यान, dhyana) includes various practices of reflection and meditation. While Jainism considers yoga and dhyana as necessary practices,[1][2] it has never been a fully developed practice,[2] but "an adjunct to austerity" to still mental and physical activity.[3] According to the Jain-canon, the only means to attain liberation is sukla-dhyāna, but essential knowledge of dhyana may have been lost early in the Jain-tradition,[4][a] and the Tattvārtha-sūtra (2nd-5th c. CE) "states that pure meditation (sukla-dhyāna, e.g. samadhi[5]) is unattainable in the current time-cycle."[6] Nevertheless, sāmāyika (equanimity) is an essential practice in Jainism.[7]

The oldest descriptions of Jain yoga and meditation can be found in the Acaranga Sutra (300 BCE),[8] which describes the solitary ascetic meditation of Mahavira. It mentions Trāṭaka (fixed gaze) meditation,[7] and uses the phrase "kāyaṃ vosajjamaṇgāre" (ĀS1, 9.3.7.), "an ascetic who has given up the body," which may be an early reference to Kayotsarga, "giving up the body,"[9] an essential Jain meditative practice, in which one stands motionless, signifying the death of the body, achieving tranquility and purity of mind,[b] resembling the three limbs of dharana, dhyana, and samadhi of Patanjali's eight limb yoga.[10] The Sutrakritanga (2nd c. BCE[11]) mentions preksha (self-observation),[12][c] and states that "the ultimate means for emancipation are dhyana, yoga and titiksa (tolerance). It also states that yoga and meditation can be completed by kayotsarga.[13]

Texts attributed to a Kundakunda (collective authorship, ca. 450 to 1150 CE)[14] incorporated samkhya, Buddhist and Advaita Vedanta influences. The 8th century Jain philosopher Haribhadra wrote the Yogadṛṣṭisamuccaya, developing his own unique system that "depart[ed] from the scriptures,"[15] assimilating many elements from Patañjali's Yoga-sūtra into his new Jain yoga.[16] The 20th century saw the development and spread of new modernist forms of Jain dhyana, including prekṣā-dhyāna of the Śvētāmbara Terāpanth-sect, which sought to rediscover Jain meditation; and the stress on direct recognition the self or atman by various teachers, and by Digambara lay-movements who are inspired by texts attributed to a Kundakunda (450-1100 CE).

Influences and practices

[edit]Adjunct to austerity

[edit]Paul Dundas notes that Jainism never “fully developed a culture of true meditative contemplation.”[17] According to Dundas, Jainism

...never fully developed a culture of true meditative contemplation, because early Jain teachings were more concerned with the cessation of mental and physical activity than their transformation, and meditation did not lose its original role as little more than an adjunct to austerity until the early medieval period, by which time it had become a subject of essentially theoretical interest. Certainly it is difficult to avoid the conclusion that later Jain writers discussed the subject only because participation in the pan-Indian socio-religious world made it necessary to do so.[3]

According to Dundas, while earliest Jainism may have had a tradition of stilling the mind inherited by highly accomplished kevalins, the knowledge of these skills was lost at an early date in the history of Jainism, leaving Jains incapable of attaining these states.[4][a]

Influences

[edit]Jainism has been influenced by other Indian religions and traditions, including yoga,[18] samkhya, Buddhism, and Advaita Vedanta. Texts attributed to a Kundakunda (collective authorship, ca. 450 to 1150 CE)[14] incorporated samkhya, Buddhist and Advaita Vedanta influences. The 8th century Jain philosopher Haribhadra assimilated many elements from Patañjali’s Yoga-sūtra into his new Jain yoga.[16]

Practices

[edit]Tapas (austerities)

[edit]According to Sagarmal Jain, "the Jain sadhana of the canonical age was centered on a three- or fourfold path of emancipation, i.e. right faith, right knowledge, right conduct, and right austerity."[10] Meditation is a form of austerity and ascetic practice (tapas),[19] which is a central feature of Jainism.[20][21][22] Ascetic life may include nakedness, symbolizing non-possession even of clothes, fasting, body mortification, and penance, to burn away past karma and stop producing new karma, both of which are believed essential for reaching siddha and moksha ("liberation from rebirths" and "salvation").[20][23][24]

Jain texts like Tattvartha Sūtra and Uttaradhyayana Sūtra discuss austerities in detail. Six outer and six inner practices are oft-repeated in later Jain texts.[25] Outer austerities include complete fasting, eating limited amounts, eating restricted items, abstaining from tasty foods, mortifying the flesh, and guarding the flesh (avoiding anything that is a source of temptation).[19] Inner austerities include expiation, confession, respecting and assisting mendicants, studying, meditation, and ignoring bodily wants in order to abandon the body.[19] Lists of internal and external austerities vary with the text and tradition.[26][27] Asceticism is viewed as a means to control desires, and to purify the jiva (soul).[22]

Kayotsarga (body-detachment) and sukla-dhyana (pure meditation)

[edit]Kayotsarga, "giving up the body," is an essential practice in the earliest texts. According to Jain-tradition, this was practiced by Mahavira when he attained liberation.[28][29]

In kayotsarga one stands motionless, "unaffected by physical surroundings as well as emotions,"[28] signifying the death of the body, and achieving tranquility and purity of mind.[b] The intense meditation described in these texts "is an activity that leads to a state of motionlessness, which is a state of inactivity of body, speech and mind, essential for eliminating karma."[28]

According to Sagarmal Jain, kayotsarga resembling the three limbs of dharana, dhyana, and samadhi of Patanjali's eight limb yoga.[10]

Sukla-dhyana (pure meditation)

[edit]Sukla-dhyana, "pure" or "clean" meditation,[30] also rendered as "abstract" meditation,[29] is another essential practice in the earliest texts, according to Jain-tradition practiced by Mahavira when he attained liberation.[28]

Sukla-dhyana] has four elements:[31][30]

- Separatory contemplation (pṛthaktva-vitarka-savicāra);

- Unitary contemplation (aikatva-vitarka-nirvicāra);

- Subtle infallible physical activity (sūkṣma-kriyā-pratipāti);

- Irreversible stillness of the soul (vyuparata-kriyā-anivarti).

The first two are said to require knowledge of the lost Jain scriptures known as purvas, and thus since ca. 150-350 CE pure meditation is considered to be no longer possible.[31] The other two forms are said in the Tattvartha sutra to be only accessible to Kevalins (enlightened ones).[32] The Tattvārtha-sūtra "states that pure meditation (sukla-dhyāna, e.g. samadhi[5]) is unattainable in the current time-cycle."[6] yet, the Jain-tradition solved this problem of non-accessibility by the mytheme of Mahavideha, a non-earthly realm were this knowledge is preserved, and people who are reborn in this realm can access this knowledge.[31]

According to Jain accounts, first attested by Jayasena (ca. 1150–1200[33]), Kundakunda visited Mahavideha receiving the teachings from Jina Simandhara, which gave Kundakunda insight into the true nature of the soul. Kanji Swami elaborated on the Kundakunda-narrative, by claiming that, in a previous life, he was present when This presence was suggested to him by Campabahen Mataji, a female disciple, who said that she also had been present then.[34]

Anuprekṣā (contemplation)

[edit]Anuprekṣā ('contemplation'),[d] also called bhāvanā ('reflection')[18] is one of the central practices of Jainism. Anuprekṣā typically refers to the twelve reflections:[35]

- anitya bhāvanā – the transitoriness of the world;[36]

- aśaraņa bhāvanā – the helplessness of the soul.[36][e]

- saṃsāra – the pain and suffering implied in transmigration;[36]

- aikatva bhāvanā – the inability of another to share one’s suffering and sorrow;[36]

- anyatva bhāvanā – the distinctiveness between the body and the soul;[36]

- aśuci bhāvanā – the filthiness of the body;[36]

- āsrava bhāvanā – influx of karmic matter;[36]

- saṃvara bhāvanā – stoppage of karmic matter;[36]

- nirjarā bhāvanā – gradual shedding of karmic matter;[36]

- loka bhāvanā – the form and divisions of the universe and the nature of the conditions prevailing in the different regions – heavens, hells, and the like;[36]

- bodhidurlabha bhāvanā – the extreme difficulty in obtaining human birth and, subsequently, in attaining true faith;[36] and

- dharma bhāvanā – the truth promulgated by Lord Jina.[36]

Sāmāyika (equanimity)

[edit]

According to Sagarma Jain, the threefold path can be summarized in sāmāyika or samatva yoga, and is "the principal concept of Jainism."[7] It is the first of the six avashyak (duties) for monks and householders.[7]

According to Padmanabh Jaini, Sāmāyika is a practice of "brief periods in meditation" in Jainism that is a part of siksavrata (ritual restraint).[37] The goal of Sāmāyika is to achieve equanimity, and it is the second siksavrata.[f]

According to Johnson, as well as Jaini, samayika connotes more than meditation, and for a Jain householder is the voluntary ritual practice of "assuming temporary ascetic status".[38] According to Dundas, samayika seems to have meant "correct behavior" in early Jainism.[39]

The samayika ritual is practiced at least three times a day by mendicants, while a layperson includes it with other ritual practices such as Puja in a Jain temple and doing charity work.[40][41][42] It consits of:[43]

- pratikramana, recounting the sins committed and repenting for them,

- pratyākhyanā, resolving to avoid particular sins in future,

- sāmāyika karma, renunciation of personal attachments, and the cultivation of a feeling of regarding every body and thing alike,

- stuti, praising the four and twenty Tīrthankaras,

- vandanā, devotion to a particular Tirthankara, and

- kāyotsarga, withdrawal of attention from the body (physical personality) and becoming absorbed in the contemplation of the spiritual Self.

Digambara self-other (body) distinction

[edit]The Digambara-tradition developed meditative parctices which center on the distinction between "self" (atman) and "other" (body),[31] akin to the Samkhya purusha-prakriti dualism.[44] Foundational in this regard are the writings by Kundakunda (collective authorship, ca. 450 to 1150 CE),[14] which show influences from Samkhya,[44] Mahayana Buddhism, and especially Advaita Vedanta,[14] reflected in the distinction between niścayanaya or ‘ultimate perspective’ and vyavahāranaya or ‘mundane perspective’, or the pure atman and the material world.[14] The recognition of this distinction is called bhed-jnan,[45] bhedvijnan, bheda-vijnana, bhedvigyan, or bhedgnan.

With the Kundakunda-texts the Digambara developed a mystical tradition focusing on the direct realization of the ultimate perspective of the pure soul.[46] Kundakunda's emphasis on liberating knowledge has become a mainstream view in Digambara Jainism,[47] and the Kundakunda-texts were an important inspiration for Shrimad Rajchandra (1867–1901), who in turn inspired Kanji Swami (1890–1980), Rakesh Jhaveri and the Shrimad Rajchandra Mission, and Dada Bhagwan (1908–1988).[48][49][50]

Pre-canonical (before 6th c. BCE)

[edit]Sagarmal Jain divides the history of Jaina yoga and meditation into five stages: 1. pre-canonical (before 6th century BCE); 2. canonical age (5th century BCE to 5th century CE); 3. post-canonical (6th century CE to 12th century CE); 4. age of tantra and rituals (13th to 19th century CE); 5. modern age (20th century on).[1]

In the pre-canonical period, Jainism developed as one of the sramana-movements in the 6th-5th century BCE, just like Buddhism, Ajivika, Samkhya and Yoga.[12]

Canonical (5th c. BCE - 5th c. CE)

[edit]

In this era, the Jain canon was recorded and Jain philosophy systematized. Sagarmal Jain notes that during the canonical age of Jaina meditation, one finds strong analogues with the 8 limbs of Patanjali Yoga, including the yamas and niyamas, through often under different names. Sagarmal also notes that during this period the Yoga systems of Jainism, Buddhism and Patanjali Yoga had many similarities.[51] Nevertheless, "the Jain sadhana of the canonical age was centered on a three- or fourfold path of emancipation, i.e. right faith, right knowledge, right conduct, and right austerity."[10]

Ācārāṅga Sūtra (3rd c. BCE) and Sutrakritanga (2nd c. BCE)

[edit]The earliest mention of yogic practices appear in early Jain canonical texts like the Ācārāṅga Sūtra (3rd c. BCE[8]), Sutrakritanga (2nd c. BCE[11]), and Rsibhasita.[12]

The Ācārāṅga Sūtra, one of the oldest Jain texts, describes the solitary ascetic meditation of Mahavira. It mentions Trāṭaka (fixed gaze) meditation,[7] and uses the phrase "kāyaṃ vosajjamaṇgāre" (ĀS1, 9.3.7.), "an ascetic who has given up the body," which may be an early reference to Kayotsarga, "giving up the body."[9] The Acaranga also mentions the tapas practice of standing in the heat of the sun (ātāpanā).[52] Mahavira's practice is described as follows:

Mahavira meditated (persevering) in some posture, without the smallest motion; he meditated in mental concentration on (the things) above, below, beside, free from desires. He meditated free from sin and desire, not attached to sounds or colours.(AS 374-375)[53]

The Ācārāṅga Sūtra states that Mahavira, after more than twelve years of austerities and meditation, entered the state of Kevala Jnana while doing "abstract meditation"[g] in a squatting position: "..in a squatting position with joined heels exposing himself to the heat of the sun, with the knees high and the head low, in deep meditation, in the midst of abstract meditation, he reached Nirvana."[29]

According to Pragya, from the Ācārāṅga Sūtra "we can conclude that Mahāvīra’s method of meditation consisted of perception and concentration in isolated places, concentration that sought to be unaffected by physical surroundings as well as emotions."[28] Pragya also notes that fasting was an important practice done alongside meditation.[54] The intense meditation described in these texts "is an activity that leads to a state of motionlessness, which is a state of inactivity of body, speech and mind, essential for eliminating karma."[28]

The Sutrakritanga mentions preksha (self-observation),[7][c] and states that "the ultimate means for emancipation are dhyana, yoga and titiksa (tolerance). It also states that yoga and meditation can be completed by kayotsarga, "giving up the body,"[13] or "to give up one's physical comfort and body movements," an essential Jain meditative practice in which one stands motionless, signifying the death of the body, and achieving tranquility and purity of mind. [b] Sagarmal Jain compares kayotsarga to the last three stages of Patanjali's eight limb of yoga, dharana, dhyana, and samadhi.[10]

The Mūlasūtras: Uttarādhyayana-sūtra and Āvaśyaka-sūtra

[edit]According to Samani Pratibha Pragya, the four mūlasūtras are important sources for early Jain meditation.[18] The Uttarādhyayana-sūtra "offers a systematic presentation of four types of meditative practices such as: meditation (dhyāna), abandonment of the body (kāyotsarga), contemplation (anuprekṣā),[h] and reflection (bhāvanā)."[18] Another meditation described in the Āvaśyaka-sūtra is meditation on the tīrthaṅkaras.[55]

Sthananga Sutra (2nd c. BCE)

[edit]The Sthananga Sutra (c. 2nd century BCE) gives a summary of four main types of meditation (dhyana) or concentrated thought. The first two are mental or psychological states in which a person may become fully immersed and are causes of bondage. The other two are pure states of meditation and conduct, which are causes of emancipation. They are:[56]

- Arta-Dhyana, "a mental condition of suffering, agony and anguish." Usually caused by thinking about an object of desire or a painful ailment;

- Raudra-Dhyana, associated with cruelty, aggressive and possessive urges;

- Dharma-Dhyana, "virtuous" or "customary" meditation, "meditation on the destruction of karma";[57]

- Sukla-Dhyana], "pure" or "clean" meditation,[30] divided into

- Separatory contemplation (pṛthaktva-vitarka-savicāra);

- Unitary contemplation (aikatva-vitarka-nirvicāra);

- Subtle infallible physical activity (sūkṣma-kriyā-pratipāti);

- Irreversible stillness of the soul (vyuparata-kriyā-anivarti).[30]

The first two are said to require knowledge of the lost Jain scriptures known as purvas and thus it is considered by some Jains that pure meditation was no longer possible. The other two forms are said in the Tattvartha sutra to be only accessible to Kevalins (enlightened ones).[32]

This broad definition of the term dhyana means that it signifies any state of deep concentration, with good or bad results.[58] Later texts like Umaswati's Tattvārthasūtra and Jinabhadra's Dhyana-Sataka (sixth century) also discusses these four dhyanas. This system seems to be uniquely Jain.[7]

Bhadrabahu II (c. 2nd c. CE) - Āvaśyaka-Niryukti

[edit]Bhadrabahu II (c. 2nd c. CE[59]) composed the Āvaśyaka-Niryukti, describing Mahavira as practicing intense austerities, fasts (most commonly three days long, as extreme as six months of fasting) and meditations. In one instance he practiced standing meditation for sixteen days and nights. He did this by facing each of the four directions for a period of time, and then turning to face the intermediate directions as well as above and below.[60]

Umāsvāti (2nd-5th c. CE) - Tattvartha Sutra

[edit]The Tattvarthasutra, composed by Umāsvāti (fl. sometime between the 2nd and 5th-century CE), is a key text which codified Jain doctrine.[61] According to the Tattvarthasutra, yoga is the sum of all the activities of mind, speech and body. Umāsvāti calls yoga the cause of "asrava" or karmic influx[62] as well as one of the essentials—samyak caritra—in the path to liberation.[62] Umāsvāti prescribed a threefold path of yoga: right conduct/austerity, right knowledge, right faith.[7] Umāsvāti also defined a series of fourteen stages of spiritual development (guṇasthāna), into which he embedded the fourfold description of dhyana.[63] These stages culminate in the pure activities of body, speech, and mind (sayogi-kevala), and the "cessation of all activity" (ayogi-kevala).[64] Umāsvāti also defined meditation in a new way (as ‘ekāgra-cintā’): "Concentration of thought on a single object by a person with good bone-joints is meditation which lasts an intra-hour (ā-muhūrta).”[65] Yet, the Tattvārtha-sūtra also "states that pure meditation (sukla-dhyāna, e.g. samadhi[5]) is unattainable in the current time-cycle."[6]

Other important figures are Jinabhadra, and Pujyapada Devanandi (wrote the commentary Sarvārthasiddhi).

Post-canonical (6th c. CE - 12th c. CE)

[edit]This period saw new texts specifically on Jain meditation and further Hindu influences on Jain yoga.

Kundakunda (400-500 CE up to 1100 CE)

[edit]This period also sees the elucidation of the practice of contemplation (anuprekṣā) with the Vārassa-aṇuvekkhā or “Twelve Contemplations”, attributed to Kundakunda[66] (collective authorship, 400-500 CE up to 1100 CE[14]). These twelve forms of reflection (bhāvanā) aid in the stopping of the influx of karmas that extend transmigration.[35]

In his Niyamasara, Kundakunda, also describes yoga bhakti—devotion to the path to liberation—as the highest form of devotion.[67]

Haribhadra

[edit]Haribhadra in the 8th century wrote the meditation compendium called Yogadṛṣṭisamuccya which discusses systems of Jain yoga, Patanjali Yoga and Buddhist yoga and develops his own unique system that are somewhat similar to these. Ācārya Haribhadra assimilated many elements from Patañjali’s Yoga-sūtra into his new Jain yoga (which also has eight parts) and composed four texts on this topic, Yoga-bindu, Yogadṛṣṭisamuccaya, Yoga-śataka and Yoga-viṅśikā.[16] Johannes Bronkhorst considers Haribhadra's contributions a "far more drastic departure from the scriptures."[15] He worked with a different definition of yoga than previous Jains, defining yoga as "that which connects to liberation" and his works allowed Jainism to compete with other religious systems of yoga.[16]

The first five stages of Haribhadra's yoga system are preparatory and include posture and so on. The sixth stage is kāntā [pleasing] and is similar to Patañjali's "Dhāraṇā." It is defined as "a higher concentration for the sake of compassion toward others. Pleasure is never found in externals and a beneficial reflection arises. In this state, due to the efficacy of dharma, one’s conduct becomes purified. One is beloved among beings and single-mindedly devoted to dharma. (YSD, 163) With mind always fixed on scriptural dharma."[68] The seventh stage is radiance (prabhā), a state of calmness, purification and happiness as well as "the discipline of conquering amorous passion, the emergence of strong discrimination, and the power of constant serenity."[69] The final stage of meditation in this system is 'the highest' (parā), a "state of Samadhi in which one becomes free from all attachments and attains liberation." Haribhadra sees this as being in "the category of “ayoga” (motionlessness), a state which we can compare with the state just prior to liberation."[69]

Acarya Haribhadra (as well as the later thinker Hemacandra) also mentions the five major vows of ascetics and 12 minor vows of laity under yoga. This has led certain Indologists like Prof. Robert J. Zydenbos to call Jainism, essentially, a system of yogic thinking that grew into a full-fledged religion.[70] The five yamas or the constraints of the Yoga Sutras of Patanjali bear a resemblance to the five major vows of Jainism, indicating a history of strong cross-fertilization between these traditions.[71][i]

Later works

[edit]Later works also provide their own definitions of meditation. The Sarvārthasiddhi of Akalanka (9th c. CE) states "only the knowledge that shines like an unflickering flame is meditation."[73] According to Samani Pratibha Pragya, the Tattvānuśāsana of Ramasena (10th c. CE) states that this knowledge is "many-pointed concentration (vyagra) and meditation is one-pointed concentration (ekāgra)."[74]

Tantric influences and ritual (13th to 19th c. CE)

[edit]

This period sees tantric influences on Jain meditation, which can be gleaned in the Jñānārṇava of Śubhacandra (11thc. CE), and the Yogaśāstra of Hemacandra (12th c. CE).[75] Śubhacandra offered a new model of four meditations:[76]

- Meditation on the corporeal body (piṇḍstha), which also includes five concentrations (dhāraṇā): on the earth element (pārthivī), the fire element (āgneyī), the air element (śvasanā/ mārutī), the water element (vāruṇī) and the fifth related to the non-material self (tattvrūpavatī).

- Meditation on mantric syllables (padastha);

- Meditation on the forms of the arhat (rūpastha);

- Meditation on the pure formless self (rūpātīta).

Śubhacandra also discusses breath control and withdrawal of the mind. Modern scholars such as Mahāprajña have noted that this system of yoga already existed in Śaiva tantra and that Śubhacandara developed his system based on the Navacakreśvara-tantra and that this system is also present in Abhinavagupta’s Tantrāloka.[76]

The Yogaśāstra of Hemacandra (12th c. CE) closely follows the model of Śubhacandra. This trend of adopting ideas from the Brāhmaṇical and tantric Śaiva traditions continues with the work of the later Śvetāmbara upādhyāya Yaśovijaya (1624–1688), who wrote many works on yoga.[77]

During the 17th century, Ācārya Vinayavijaya composed the Śānta-sudhārasabhāvanā in Sanskrit which teaches sixteen anuprekṣā, or contemplations.[78]

Modern (20th-21st c. CE)

[edit]

The growth and popularity of mainstream Yoga and Hindu meditation practices influenced a revival in various Jain communities, especially in the Śvētāmbara Terapanth order. These systems sought to "promote health and well-being and pacifism, via meditative practices as “secular” nonreligious tools."[79] 20th century Jain meditation systems were promoted as universal systems accessible to all, drawing on modern elements, using new vocabulary designed to appeal to the lay community, whether Jains or non-Jains.[80] It is important to note that these developments happened mainly among Śvētāmbara sects, while Digambara groups generally did not develop new modernist meditation systems.[81] Digambara sects instead promote the practice of self-study (Svādhyāya) as a form of meditation, influenced by the work of Kundakunda. This practice of self study (reciting scriptures and thinking about the meaning) is included in the practice of equanimity (sāmāyika) which is the spiritual practice emphasized by 20th century Digambara sects.[82]

Terāpanth prekṣā-dhyāna

[edit]The modern era saw the rise of a new Śvētāmbara sect, the Śvetāmbara Terapanth, founded by Ācārya Bhikṣu (1726–1803).[83] Tulasī (1914–1997), the ninth Acharya of the Terapanth Sangha, and his student Ācārya Mahāprajña (1920– 2010) sought to rediscover Jain meditation and developed a system termed prekṣā-dhyāna. It includes "meditative techniques of perception, kayotsarg, anupreksha, mantra, posture (āsana), breath control (prāṇāyāma), hand and body gestures (mudrā), various bodily locks (bandha), meditation (dhyāna) and reflection (bhāvanā),"[84] "intersect[ing] with the global yoga market".[85] Despite the innovations, the meditation system is said to be firmly grounded in the classic Jain metaphysical mind body dualism in which the self (jiva, characterized by consciousness, cetana which consists of knowledge, jñāna and intuition, darśana) is covered over by subtle and gross bodies.[86]

Prekṣā means "to perceive carefully and profoundly". In prekṣā, perception is an impartial experience bereft of the duality of like and dislike, pleasure and pain, attachment or aversion.[87] Meditative progress proceeds through the different gross and subtle bodies, differentiating between them and the pure consciousness of jiva. Mahāprajña interprets the goal of this to mean to “perceive and realise the most subtle aspects of consciousness by your conscious mind (mana).”[88] Important disciplines in the system are synchrony of mental and physical actions, present-mindedness or complete awareness of one's actions, disciplining the reacting attitude, friendliness, diet, silence, spiritual vigilance.[89]

The prekṣā system uses an eight limb hierarchical schema, where each one is necessary for practicing the next:[90]

- Relaxation (kāyotsarga), abandonment of the body, also “relaxation (śithilīkaraṇa) with self-awareness,” allows vital force (prāṇa) to flow.

- Internal Journey (antaryātrā), this is based on the practice of directing the flow of vital energy (prāṇa-śakti) in an upward direction, interpreted as being connected with the nervous system.

- Perception of Breathing (śvāsaprekon), of two types: (1) perception of long or deep breathing (dīrgha-śvāsa-prekṣā) and (2) perception of breathing through alternate nostrils (samavṛtti-śvāsa-prekṣā).

- Perception of Body (śarīraprekṣā), one becomes aware of the gross physical body (audārika-śarīra), the fiery body (taijasa-śarīra) and karmic body (karmaṇa-śarīra), this practice allows one to perceive the self through the body.

- Perception of Psychic Centres (caitanyakendra-prekṣā), defined as locations in the subtle body that contain ‘dense consciousness’ (saghana-cetanā), which Mahāprajña maps into the endocrine system.

- Perception of Psychic Colors (leśyā-dhyāna), these are subtle consciousness radiations of the soul, which can be malevolent or benevolent and can be transformed.

- Auto-Suggestion (bhāvanā), Mahāprajña defines bhāvanā as “repeated verbal reflection”, infusing the psyche (citta) with ideas through strong resolve and generating "counter-vibrations" which eliminate evil impulses.

- Contemplation (anuprekṣā), contemplations are combined with the previous steps of dhyana in different ways. The contemplations can often be secular in nature.

Contemplation (anupreksa) themes are impermanence, solitariness, and vulnerability. Regular practice is believed to strengthen the immune system and build up stamina to resist against aging, pollution, viruses, diseases. Meditation practice is an important part of the daily lives of the religion's monks.[91][better source needed]

Mahāprajña also taught subsidiary limbs to prekṣā-dhyāna, which would help support the meditations in a holistic manner, these are Prekṣā-yoga (posture and breathing control) and Prekṣā-cikitsā (therapy).[92] Mantras such as Arham are also used in this system.[93]

Kundakunda-inspired lay-movements

[edit]The Digambara text Pravacanasara, attributed to a Kundakunda but probably the result of multiple authorship over multiple centuries, states that a Jain mendicant should meditate on "I, the pure self." Anyone who considers his body or possessions as "I am this, this is mine" is on the wrong road, while one who meditates, thinking the antithesis and "I am not others, they are not mine, I am one knowledge" is on the right road to meditating on the "soul, the pure self".[94][j] The texts attributed to Kundakunda inspired two contemporary lay-movements within Jainism with his notion of two truths and his emphasis on direct insight into niścayanaya or ‘ultimate perspective’, also called “supreme” (paramārtha) and “pure” (śuddha).[k]

Shrimad Rajchandra (1867-1901) was a Jain poet and mystic who was inspired by works of Kundakunda and Digambara mystical tradition. He in turn inspired the Kanji Panth, a lay movement founded by Kanji Swami (1890-1980),[48] and also inspired Dada Bhagwan,[49] Rakesh Jhaveri (Shrimad Rajchandra Mission), Saubhagbhai, Lalluji Maharaj (Laghuraj Swami), Atmanandji and several other religious figures. Bauer notes that "[in] recent years there has been a convergence of the Kanji Swami Panth and the Shrimad Rajcandra movement, part of trend toward a more eucumenical and less sectarian Jainism among educated, mobile Jains living overseas."[50]

Other teachers

[edit]Citrabhānu (1922-2019) was a Jain monk who moved to the West in 1971, and founded the first Jain meditation center in the world, the Jaina Meditation International Centre in New York City. He eventually married and became a lay teacher of a new system called "Jain meditation" (JM), on which he wrote various books.[100] The core of his system consists of three steps (tripadī): 1. who am I? (kohum), 2. I am not that (nahum) (not non-self), 3. I am that (sohum) (I am the self). He also makes use of classic Jain meditations such as the twelve reflections (thought taught in a more optimistic, modern way), Jaina mantras, meditation on the seven chakras, as well as Hatha Yoga techniques.[101]

Ācārya Suśīlakumāra (1926–1994) of the Sthānakavāsī tradition founded “Arhum Yoga” (Yoga on Omniscient) and established a Jain community called the “Arhat Saṅgha” in New Jersey in 1974.[102] His meditation system is strongly tantric and employs mantras (mainly the namaskār), nyasa, visualization and chakras.[103]

The Sthānakavāsī Ācārya Nānālāla (1920–1999), developed a Jaina meditation called Samīkṣaṇa-dhyāna (looking at thoroughly, close investigation) in 1981.[104] The main goal of samīkṣaṇa-dhyāna is the experience of higher consciousness within the self and liberation in this life.[105] Samīkṣaṇa-dhyāna is classified into two categories: introspection of the passions (kaṣāya samīkṣaṇa) and samatā-samīkṣaṇa, which includes introspection of the senses (indriya samīkṣaṇa), introspection of the vow (vrata samīkṣaṇa) introspection of the karma (karma samīkṣaṇa), introspection of the Self (ātma samīkṣaṇa) and others.[106]

Bhadraṅkaravijaya (1903–1975) of the Tapāgaccha sect founded “Sālambana Dhyāna” (Support Meditation). According to Samani Pratibha Pragya, most of these practices "seem to be a deritualisation of pūjā in a meditative form, i.e. he recommended the mental performance of pūjā." These practices (totally 34 different meditations) focus on meditating on arihantas and can make use of mantras, hymns (stotra), statues (mūrti) and diagrams (yantra).[107]

Ācārya Śivamuni (b. 1942) of the Śramaṇa Saṅgha is known for his contribution of “Ātma Dhyāna” (Self-Meditation). The focus in this system is directly meditating on the nature of the self, making use of the mantra so’ham and using the Ācārāṅga Sūtra as the main doctrinal source.[108]

Muni Candraprabhasāgara (b. 1962) introduced “Sambodhi Dhyāna” (Enlightenment-Meditation) in 1997. It mainly makes use of the mantra Om, breathing meditation, the chakras and other yogic practices.[109]

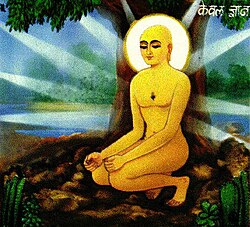

Iconography

[edit]

According to Jain-tradition, meditation derives from Rishabhanatha, the first tirthankara.[12] Jains believe that all twenty-four Tirthankaras practiced deep meditation, some for years and some for months, and attained enlightenment. All the statues and pictures of Tirthankaras primarily show them in meditative postures.[110][111][better source needed]

See also

[edit]- Buddhist meditation

- Hindu meditation

- Jewish meditation

- Christian meditation

- Muraqaba

- Daoist meditation

Notes

[edit]- ^ a b Compare Theravada Buddhism, which by the time of Buddhaghosa (5th c. CE) had developed an extensive comentarial tradition, but seems to have lost the knwledge and skills to attain jnana. The 19th and 20th century saw a revival of interest ij meditation-techniques.

- ^ a b c See Wisdom Library, Kayotsarga

- ^ a b Jain, Sagarmal (2015): "Perception. Sanskrit: Prekṣā derived from the root 'iksa', which means 'to see'. When the prefix 'pra' is added, it becomes pra + iksa = preksa, which means to perceive carefully and profoundly what is experienced within to observe within the philosophy of experiencing the self."

- ^ See also Wisdom Library, Anupreksha, Anuprekṣā: 3 definitions.

- ^ According to the Jain text, Sarvārthasiddhi: There is no escape for the young one of a deer pounced upon by a hungry tiger fond of the flesh of animals. Similarly, there is no way of escape for the self caught in the meshes of birth, old age, death, disease and sorrow. Even the stout body is helpful in the presence of food, but not in the presence of distress. And wealth acquired by great effort does not accompany the self to the next birth. The friends who have shared the joys and sorrows of an individual cannot save him at his death. His relations all united together cannot give him relief when he is afflicted by ailment. But if he accumulates merit or virtue, it will help him to cross the ocean of misery. Even the lord of devas cannot help anyone at the point of death. Therefore virtue is the only means of succour to one in the midst of misery. Friends, wealth, etc. are also transient. And so there is nothing else except virtue which offers succour to the self. To contemplate thus is the reflection on helplessness. He, who is distressed at the thought that he is utterly helpless, does not identify himself with thoughts of worldly existence. And endeavours to march on the path indicated by the Omniscient Lord.

- ^ The first is desavakasika (staying in a restrained surrounding, cutting down worldly activities). The third is posadhopavasa (fasting on the 8th and 14th days on lunar waxing and waning cycles). The fourth is dana (giving alms to Jain monks, nuns or spiritual people).[37]

- ^ Wisdom Library, Abstract meditation: Trishashti Shalaka Purusha Caritra: "Deep concentration on ideas or concepts that are beyond physical reality."; Acaranga-sutra: "A mode of profound contemplation that some individuals neglect in favor of sensual pleasures."

- ^ See also Wisdom Library, Anupreksha, Anuprekṣā: 3 definitions.

- ^ Worthington writes, "Yoga fully acknowledges its debt to Jainism, and Jainism reciprocates by making the practice of yoga part and parcel of life."[72]

- ^ This meditative focus contrasts with the anatta focus of Buddhism, and the atman focus in various vedanta schools of Hinduism such as advaita and vishistadvaita schools.[95][96]

- ^ According to Long, this view shows influence from Buddhism and Vedanta, which see bondage are arising from avidya, ignorance, and see the ultimate solution to this in a form of spiritual gnosis.[97] Johnson also notes that "his use of a vyavahara/niscaya distinction [...] has more in common with Madhyamaka Buddhism and even more with Advaita Vedanta than with the Jain philosophy of Anekantavada."[98] Cort, referring to Johnson, notes that "a minority position exemplified by Kundakunda has deemphasized conduct and focused upon knowledge alone."[99]

References

[edit]- ^ a b Jain, Sagarmal 2015, p. 14.

- ^ a b Dundas 2002, pp. 166–169.

- ^ a b Dundas 2002, pp. 166–167.

- ^ a b Dundas 2002, pp. 167.

- ^ a b c Jain, Sagarmal 2015, p. 17.

- ^ a b c Pragya 2017, p. 255.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Jain, Sagarmal 2015.

- ^ a b Key Chapple 2008, p. 45.

- ^ a b Pragya 2017, pp. 58.

- ^ a b c d e Jain, Sagarmal 2015, p. 18.

- ^ a b Bronkhorst 2020.

- ^ a b c d Jain, Sagarmal 2015, p. 15.

- ^ a b Jain, Sagarmal 2015, p. 15-16.

- ^ a b c d e f Balcerowicz 2023, p. 122.

- ^ a b Bronkhorst 1993a, p. 151-162.

- ^ a b c d Pragya 2017, p. 79.

- ^ Dundas 2002, pp. 143–144.

- ^ a b c d Pragya 2017, p. 42.

- ^ a b c Cort 2001a, pp. 120–122.

- ^ a b Cort 2001a, pp. 118–122.

- ^ Qvarnström 2003, p. 113.

- ^ a b Qvarnström 2003, pp. 169–174, 178–198 with footnotes.

- ^ Qvarnström 2003, pp. 205–212 with footnotes.

- ^ Balcerowicz 2015, pp. 144–150.

- ^ Cort 2001a, pp. 120–21.

- ^ Qvarnström 2003, p. 182 with footnote 3.

- ^ Johnson 1995, pp. 196–197.

- ^ a b c d e f Pragya 2017, p. 52.

- ^ a b c Jacobi 1964.

- ^ a b c d Wisdom Library, Sukla-Dhyana

- ^ a b c d Pragya 2020, p. 178.

- ^ a b Pragya 2017, pp. 73, 225.

- ^ Balcerowicz 2023, p. 120.

- ^ "Jainism". Philtar.ac.uk. Retrieved 22 December 2017.

- ^ a b Jain 2012, pp. 149–150.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l "Jainism Literature Center - Jain Education". sites.fas.harvard.edu. Archived from the original on 8 May 2021. Retrieved 8 January 2021.

- ^ a b Jaini 1998, pp. 180–181.

- ^ Johnson 1995, pp. 189–190.

- ^ Dundas 2002, p. 170.

- ^ Jaini 1998, pp. 180–182.

- ^ S.A. Jain 1992, p. 261.

- ^ Natubhai Shah 2004, pp. 128–131.

- ^ Jain, Champat Rai 1917, p. 45.

- ^ a b Bronkhorst 2015, p. 43.

- ^ Parson 2019.

- ^ Long 2013, p. 65-66.

- ^ Long 2013, p. 128.

- ^ a b Shaw, Richard.

- ^ a b Flügel 2005, p. 194–243.

- ^ a b Bauer 2004, p. 465.

- ^ Jain, Sagarmal 2015, p. 16.

- ^ Pragya 2017, p. 93.

- ^ Jacobi 1884.

- ^ Pragya 2017, p. 51.

- ^ Pragya 2017, p. 105.

- ^ Pragya 2017, pp. 66–75.

- ^ Wisdom Library, Dharma-Dhyana

- ^ Pragya 2017, p. 67.

- ^ Pragya 2017, p. 29.

- ^ Pragya 2017, pp. 53–55.

- ^ Mahapragya 2004.

- ^ a b Tattvarthasutra [6.2]

- ^ Pragya 2017, pp. 68, 76.

- ^ Pragya 2017, p. 77.

- ^ Pragya 2017, pp. 73–74.

- ^ Pragya 2017, p. 66.

- ^ Niyamasara [134-40]

- ^ Pragya 2017, p. 81.

- ^ a b Pragya 2017, p. 82.

- ^ Zydenbos, Robert. "Jainism Today and Its Future." München: Manya Verlag, 2006. p.66

- ^ Zydenbos (2006) p.66

- ^ Worthington, p. 35.

- ^ Pragya 2017, p. 46.

- ^ Pragya 2017, pp. 46–47.

- ^ Pragya 2017, pp. 43, 82.

- ^ a b Pragya 2017, p. 83.

- ^ Pragya 2017, p. 86.

- ^ Pragya 2017, pp. 86–87.

- ^ Pragya 2017, p. 249.

- ^ Pragya 2017, p. 251.

- ^ Pragya 2017, p. 254.

- ^ Pragya 2017, p. 256.

- ^ Pragya 2017, p. 92.

- ^ Pragya 2017, pp. 89–90.

- ^ Jain 2015, p. xi.

- ^ Pragya 2017, pp. 180–181.

- ^ Acharya MahapragyaAcharya Mahapragya Key (1995). "01.01 what is preksha". The Mirror Of The Self. JVB, Ladnun, India.

- ^ Pragya 2017, p. 182.

- ^ Acharya MahapragyaAcharya Mahapragya Key (1995). "2 path and goal". The Mirror Of The Self. JVB, Ladnun, India.

- ^ Pragya 2017, pp. 186–196.

- ^ J. Zaveri What is Preksha? Archived 25 January 2008 at the Wayback Machine. .jzaveri.com. Retrieved on: 25 August 2007.

- ^ Pragya 2017, p. 199.

- ^ Pragya 2017, p. 205.

- ^ Johnson 1995, pp. 137–143.

- ^ Bronkhorst 1993, pp. 74, 102, Part I: 1–3, 10–11, 24, Part II: 20–28.

- ^ Mahony 1997, pp. 171–177, 222.

- ^ Long 2013, p. 127.

- ^ Johnson 1995, p. 137.

- ^ Cort 1998, p. 10.

- ^ Pragya 2017, pp. 260–261.

- ^ Pragya 2017, p. 262.

- ^ Pragya 2017, pp. 267–268.

- ^ Pragya 2017, pp. 270–271.

- ^ Pragya 2017, p. 274.

- ^ Pragya 2017, p. 277.

- ^ Pragya 2017, pp. 278–279.

- ^ Pragya 2017, p. 284.

- ^ Pragya 2017, p. 295.

- ^ Pragya 2017, pp. 297–300.

- ^ Roy Choudhury, Pranab Chandra (1956). Jainism in Bihar. Patna: I.R. Choudhury. p. 7.

- ^ The Story Of Gommateshwar Bahubali, archived from the original on 31 October 2010, retrieved 21 July 2010

Sources

[edit]- Balcerowicz, Piotr (2015), Early Asceticism in India: Ājīvikism and Jainism, Routledge, ISBN 978-1-317-53853-0

- Balcerowicz, Piotr (2023). "Kundakunda, A 'Collective Author': Deconstruction of a Myth". In Flugel, Peter; De Jonckheere, Heleen; Sohnen-Tieme, Renate (eds.). Pure Soul: The Jaina Spiritual Traditions. Centre of Jain Studies, SOAS.

- Bauer, Jerome (2004). "Kanji Swami (1890-1980)". In Jestice, Phyllis G. (ed.). Holy People of the World: A Cross-Cultural Encyclopedia. Vol. 1. ABC-CLIO. p. 464. ISBN 9781576073551.

- Bronkhorst, Johannes (1993), The Two Traditions of Meditation in Ancient India, Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN 978-81-208-1114-0

- Bronkhorst, Johannes (1993a). "Remarks on the History of Jaina Meditation". In Smet, Rudy; Watanabe, Kenji (eds.). Jain Studies in Honour of Jozef Deleu. Tokyo: Hon-no-Tomosha.

- Bronkhorst, Johannes (2020). "The Formative Period of Jainism (c. 500 BCE-200 CE)". Brill's Encyclopedia of Jainism.

- Cort, John E., ed. (1998), Open Boundaries: Jain Communities and Cultures in Indian History, SUNY Press, ISBN 978-0-7914-3785-8

- Cort, John E. (2001a), Jains in the World : Religious Values and Ideology in India, Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0-19-513234-2

- Dundas, Paul (2002) [1992], The Jains (Second ed.), London and New York: Routledge, ISBN 978-0-415-26605-5

- Flügel, Peter (2005), King, Anna S.; Brockington, John (eds.), "Present Lord: Simandhara Svami and the Akram Vijnan Movement" (PDF), The Intimate Other: Love Divine in the Indic Religions, New Delhi: Orient Longman, ISBN 978-81-250-2801-7

- Jacobi, Hermann (1884), F. Max Müller (ed.), The Ācāranga Sūtra, Sacred Books of the East vol.22, Part 1, Oxford: The Clarendon Press, ISBN 0-7007-1538-X

{{citation}}: ISBN / Date incompatibility (help) - Jacobi, Hermann (1964). Jaina Sutras Part I. Osmania University, Digital Library Of India. Motilal Babarsidass.

- Jain, Andrea (2015). Selling Yoga : from Counterculture to Pop Culture. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-939024-3. OCLC 878953765.

- Jain, Champat Rai (1917), The Householder's Dharma: English Translation of The Ratna Karanda Sravakachara, The Central Jaina Publishing House

- Jaini, Padmanabh S. (1998) [1979], The Jain Path of Purification, Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN 978-81-208-1578-0

- Jain, S. A. (1992) [First edition 1960], Reality (English Translation of Srimat Pujyapadacharya's Sarvarthasiddhi) (Second ed.), Jwalamalini Trust

- Jain, Sagarmal (2015). "The Historical development of the Jaina yoga system and the impacts of other Yoga systems on Jaina Yoga". In Key Chapple, Christopher (ed.). Yoga in Jainism. Routledge.

- Jain, Vijay K. (2012), Acharya Amritchandra's Purushartha Siddhyupaya, Vikalp Printers, ISBN 9788190363945

- Johnson, W.J. (1995), Harmless Souls: Karmic Bondage and Religious Change in Early Jainism with Special Reference to Umāsvāti and Kundakunda, Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN 978-81-208-1309-0

- Key Chapple, Christopher (2008). Yoga and the Luminous: Patañjali's Spiritual Path to Freedom. SUNY Press.

- Long, Jeffery D. (2013), Jainism: An Introduction, I.B. Tauris, ISBN 978-0-85771-392-6

- Mahapragya (2004). "Foreword". Jain Yog. Aadarsh Saahitya Sangh.

- Mahony, William (1997), The Artful Universe: An Introduction to the Vedic Religious Imagination, State University of New York Press, ISBN 978-0-7914-3580-9

- Pragya, Samani Pratibha (2017), Prekṣā meditation: history and methods. PhD Thesis, SOAS, University of London

- Pragya, Samani Pratibha (2020). "yoga and meditation in the jain tradition". In Newcombe, Suzanne; O’Brien-Kop, Karen (eds.). Routledge Handbook of Yoga and Meditation Studies. Routledge.

- Qvarnström, Olle, ed. (2003), Jainism and Early Buddhism: Essays in Honor of Padmanabh S. Jaini, Jain Publishing Company, ISBN 978-0-89581-956-7

- Shah, Natubhai (2004) [1998], Jainism: The World of Conquerors, vol. I, Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN 978-81-208-1938-2

- Shaw, Richard. "Kanji swami Panth". University of Cumbria. Division of Religion and philosophy. Retrieved 21 February 2013.

External links

[edit] Media related to Jain meditation at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Jain meditation at Wikimedia Commons